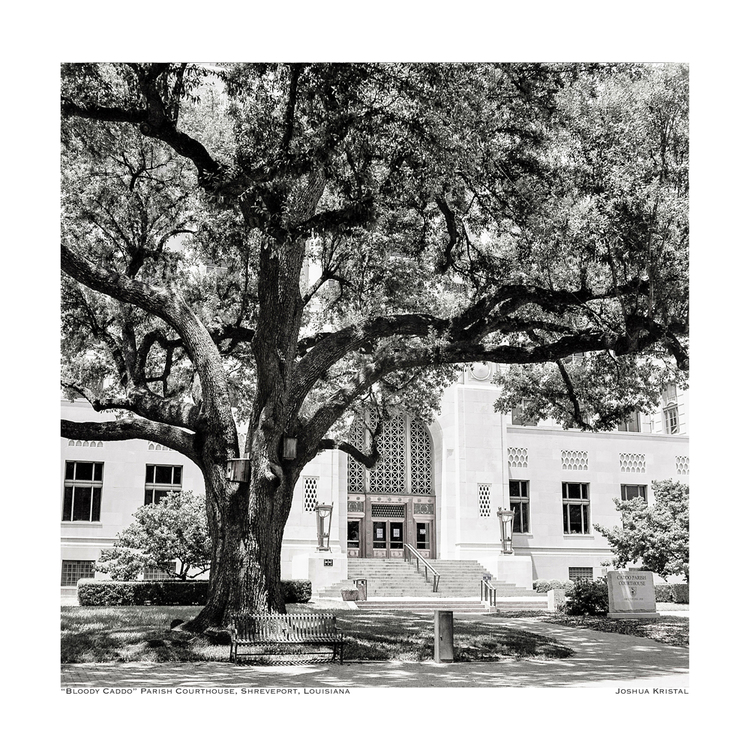

Southernscapes, Joshua's installation for the SfDM, consists of two series, one black and white, one color, both taken during a road trip through the American South in 2011. The trip was inspired by James Allen's 2001 book, Without Sanctuary, documenting the disturbing visual legacy of postcards and photographic souvenirs taken at public lynchings in the United States between 1882 and 1950. Deeply moved by this tragic history, Joshua set out to find some of the sites where lynchings had occurred in order to memorialize these now-anonymous places that have faded back into the landscape, a willfully forgotten chapter in our nation's past. Each photograph depicts a place where a specific lynching occurred -- a tree in front of a Shreveport courthouse, a field along an Arkansas highway, a railroad bridge in Alabama, an oak tree in Mississippi. The name of the victim and the year of the lynching are written below each image, the most recent of which occurred in 2010. At first glance, these photographs are remarkable for their tranquility -- and, in contrast to much of Joshua's work, the absence of people in the frame. The portraits of the trees, in particular, are regal and betray no hint of the brutality that haunts them. With nothing to commemorate the lives taken there, these sites occupy a secret history unknown to those who may pass by. Inspired by the Emmett Till Memorial Highway in Mississippi, commemorating the Chicago teenager murdered in 1955 for allegedly flirting with a white woman, Joshua aims to create a similar memorial to these events in the belief that reckoning with this history and its victims is a necessary step toward collective healing.

In contrast to the solemnity of the lynching series, the four photos that make up the Baby Beauty Pageant series are all color and tackiness; yet they depict a more subtle violence. During his southern sojourn, Joshua happened upon a baby beauty pageant in a small town in Mississippi. After talking his way into the event and roaming for about an hour, he was ejected by officials, but not before capturing some compelling moments. These images depict the kind of crude enforcement of the gender roles that appear marginal and quirky in a small town beauty pageant like this one, yet as Frank Rich describes in his 1997 essay on our national obsession with JonBenet Ramsay, beauty pageants like these are big business in the U.S. and the themes and messages about gender and sexuality as acted out by their tiny participants have made their way into the culture writ large.

There is no question that these photographs, formally quite beautiful, yet complicated in what they portray, will be interesting to live with for the duration of this exhibition. They will most certainly shape the conversation that happens within these walls - when neighbors stop by, when we have dinner parties, or when people come to see the gallery by appointment - which is why we undertook this endeavor in the first place.

If you would like to view these images in situ, please contact domesticmuseology@gmail.com for an appointment. A limited number of prints are also available for sale. To see more of Joshua Kristal's work, visit his website: joshuakristal.com or his blog: http://machupicchuthis.wordpress.com/

OPENING

On September 24th, we opened our fall exhibition at the Society for Domestic Museology. SouthernScapes is made up of two series of photographs by Joshua Kristal. Both were taken in the American South, and that is where the similarities end. Or do they? In keeping with the geographic theme, we went southern with the food for the opening: brisket sliders with coleslaw, baby-back ribs, macaroni and cheese, Ritz crackers with pimento cheese spread and collard greens... Our apartment smelled like a smokehouse.

There were 10 photos in all, and between the two series, we expanded out of our conventional "exhibition" space and installed photographs in the hallway. One of the issues with a domestic gallery such as ours is the substandard lighting, which proved to be a challenge in the long, narrow space, where the photos were barely visible. With only about two hours to go until the opening, Joshua MacGyvered some hallway gallery lighting by re-purposing some random lamps from around the apartment and securing them to the wall with blue painter's tape.

Of all of the work that we have shown here (and granted this is only our first year), Southernscapes is the most challenging in terms of subject matter. Upon first glance the photos are either serene and beautiful (if you're looking at the black and white series) or curious and eccentric (the color photos), but upon closer study, they are each disturbing in their own way. After about an hour or so of mingling around with ribs and Ritz crackers in hand, we gathered around to hear Joshua talk about his work.

The black-and-white photographs are images of places curiously devoid of people, which is a striking departure from Joshua's usual focus. As he explained, this series was inspired by the book Without Sanctuary, which documents the strange and horrific history of lynching in this country and the even stranger, more horrific trade in postcards commemorating these events. This photo series is the beginning of a larger project that Joshua would like to continue -- one that goes back and documents these now vacant spaces in order to commemorate and acknowledge these events. The conversation that followed ranged from talking specifically about the photos (Do they qualify as landscapes? Should the descriptions be part of the photograph or part of the wall text?) to the unwieldy issues they represent (How do these images, while beautiful as photographs, read against the horror of the postcards? And what does that kind of cruel voyeurism say about us?)

We tend to think of this as a Southern phenomenon, yet lynchings occurred everywhere in the US. How does one commemorate appropriately? There was an acknowledged irony to our gathering of all-white urbanites, eating southern-fare and talking about this subject. But that is exactly the point: being confronted with these photographs is to realize that we are all complicit in this story.

The second group of photos, candid moments from a baby beauty pageant in Mississippi, tells another tale, one that we might also like to think of as a "southern" phenomenon but is all too universal. Happening across a small-town beauty pageant where the contestants were all under the age of 3, Joshua spent about an hour capturing this ritual that at once seems so fringe and weird but has everything to say about kids, gender and sexuality. Then he got kicked out.

In our comfortable domestic setting, the theme of the conversation that evening was violence, from the overt violence of the public lynchings to the subtle violence that happens when you dress up your toddler in a ball gown and tiara (or a bathing suit!) and parade her down the catwalk. My favorite thing about these openings has been the conversation that happens around the work. What starts as a party with food, drinks, and small talk evolves into an earnest discussion about art and ideas, devoid of irony. The kind that can be hard to find sometimes.

For almost a month we have been living with this installation, and it sneaks up on you. Now that I have gotten used to the transformation of our space, I find myself puttering around at home, oblivious to my surroundings in a way, until I look up and am jarred into really looking at the work we have on the walls and what it represents. I feel guilty about enjoying the formal beauty of the trees and absurdity of the pageant photos. While our kids want to know why we took down the pictures of our family and replaced them with pictures of people none of us knows, they haven't asked about the black-and-white photos yet. I've also found it to be an interesting social experiment to see who notices the work when they come into the room and who doesn't bother to look. After all, we're not a gallery; just an apartment with things on the wall, right?

CLOSING

Last week, we gathered people together for the closing of Joshua Kristal's showing of Southernscapes, a photo series we have been living with for the past two months. We kept to the Southern food theme again, making chili, cornbread and - my personal favorite - a pineapple-pecan-cream-cheese-ball. Yes, that is actually a thing. About 20 or so people wandered the apartment looking at Joshua's work. The mood was festive.

In what has become a SfDM tradition, about midway through the evening we gathered everyone around the living room to hear Joshua talk about his projects. I was curious to see the same work discussed for a second time, with a new set of visitors. The Baby Beauty Pageant series was already hanging on the wall, so we started there, which was appropriate because when I originally approached Joshua about exhibiting his work in our "domestic gallery", this was the series he chose because of its connection to family life. And if these five photos had been the only ones on view, we could have easily spent the whole evening talking about pageantry and gender identity and the kinds of subcultures on which Joshua often casts his lens. But as it happened, these images ended up getting short shrift, acting as an incongruous warm up to the much bigger project: the lynching series.

There is no question that the lynching series is difficult work. Despite their formal beauty, the photographs - especially when coupled with the book that inspired them, Without Sanctuary- represent an ugliness that is really hard to face head on, yet can't be ignored. Over the past two months, amidst the unrest in Ferguson and the outrage around the death of Eric Garner, these haunting landscapes have been a daily reminder of the dark history that has shaped current events. It seemed fitting that we were all gathered, on the very same evening as the Michael Brown verdict was to be announced, to talk about a project that aims to highlight this history in the interest of moving toward some kind of healing.

This time, the conversation was less about the formal merits of the photographs as works of art, and much more about the issues they represent: racial injustice and the violence that enforces it. The kind of thing we never talk about. And by we, I mean white people. Or maybe I just mean me (perhaps it's better if I just speak for myself here). Why? Well, because it's uncomfortable and, honestly, pretty easy to avoid (when you're white). I haven't had a full-fledged "conversation about race" since I was an undergraduate in the early nineties and even now the thought makes me cringe. My generation prefers irony and sarcasm to unvarnished truth. Once you're a card-carrying adult, burdened with the daily grind of existing and relieved of the luxury of time that dorm-living provides, it's surprisingly easy to avoid heavy topics of all kinds. But the real reason I think we avoid the topic is fear. Fear of saying the wrong thing, fear of shaking up a comfortable world view, and the biggest fear of all: if you are white, how do you make sense of the possibility that your own great-great grandparents, by virtue of their own whiteness, were complicit in this history? And how does that trickle down to now?

With that in mind, I was feeling very self-conscious about the fact that our gathering was made up primarily (but not all) of white folks. What right do we have to this discussion? While there were a few people of color in attendance, by the time we got to talking the crowd had thinned a bit making it a conversation of mostly white people and one young woman who was a first generation African American. In addition to being saddled with a healthy dose of white liberalism, I'm also from the Midwest, which makes me innately averse to conflict and uncomfortable situations of any kind. Yet here I was, in my own living room, moderating what was shaping up to be a fairly honest and raw conversation about race, in all of its messy discomfort and intensity, thanks mostly to the bravery of one woman who was willing to engage a roomful of people and shake things up a bit. She said things that needed to be heard and I would like to think she was. The discussion itself wasn't all that groundbreaking, but the fact that it happened felt important. When was the last time you went to a party, ended up really engaging in a difficult conversation that left you thinking? For me it was probably 1993. Maybe it's time to take that up again.

A few days after our event, the Quartz article entitled, 12 Things White People Can Do Now Because of Ferguson, was recirculated. Originally published in August, it is a powerful piece of writing that gets to the heart of why all of us - and by that I mean white people (duh)- need to be more proactive in speaking up. This convergence of events has made me think differently about Joshua's series of photographs. While the larger goal of creating tangible memorials in these places is worthy of pursuit, it is the photographs themselves, I think, that have the power to create change. Perhaps they should just be passed around from living room to living room as catalysts to get people to start really talking about those things we have spent too much time avoiding. While we will soon be saying goodbye to this series, I will be keeping one photograph: the tree that marks the site of the lynching of Frederick Jermaine Carter in 2010. I'm keeping it because it is both beautiful and terrible. And because it will a reminder to keep the conversation going.